How pot still works?

A pot still operates on a straightforward principle: heat a liquid containing alcohol, allow the alcoholic vapors to boil off, direct those vapors to a cooling area, and condense them back into liquid. Whisky, despite its rich flavors, is primarily a mix of ethanol and water. The compounds that create its distinctive aromas are just a tiny fraction of the mixture.

The Basics of Pot Still Technology

Pot stills have remained largely unchanged for centuries. Modern pot stills may have additional features, but their core structure is the same. To distill beer into whisky, you need:

A heat source

A vessel to hold and heat the beer.

A space to direct the alcoholic vapors away from the beer.

An apparatus to condense the vapors back into liquid.

Heating Methods

Historically, pot stills were heated with direct flames. This method is now rare, except in the Cognac industry. Today, most pot stills use steam to heat the beer, either through jackets surrounding the pot or coils inside it. The steam heats the beer, causing it to boil. At around 94°C, alcohol-enriched vapors rise above the beer.

The Role of the Neck and Lyne Arm

The neck and lyne arm of the still direct these vapors away from the boiling liquid. The shape and height of the neck significantly affect the flavor and aroma of the whisky. Taller necks cause some vapors to condense and return to the pot, producing a more delicate distillate. The angle of the lyne arm also matters. An upward angle promotes internal reflux, leading to lighter spirits, while a downward angle results in heavier flavors.

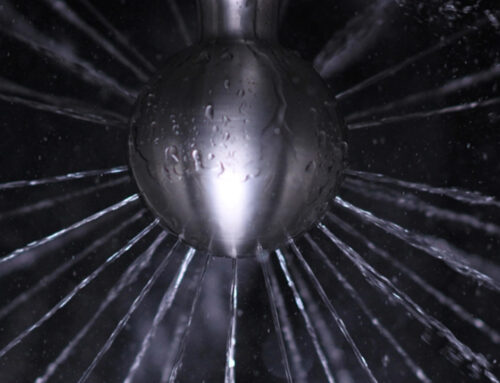

Condensation and Copper Interaction

Once the vapors reach the condenser, they are cooled back into liquid. The interaction between the vapors and the copper in the condenser is crucial. Copper removes unwanted sulphurous aromas and enhances fruity esters. Modern shell and tube condensers maximize copper contact, producing cleaner and fruitier spirits.

The Distillation Process

Most pot stills used for single malts require two distillation passes. The first distillation turns an 8% ABV beer into a 25% ABV “low wine.” The second distillation concentrates the low wine to around 70% ABV. During the second pass, the distiller makes “cuts” to separate the desirable parts of the spirit from the undesirable ones. The initial distillate, or “heads,” often has solvent aromas and is not kept. The distiller waits for the “hearts,” the high-quality portion, and collects it. As the distillation continues, the flavors turn bitter or sour, leading to the “tails,” which can be recycled in the next batch.

Despite technological advances, the basic function of pot stills remains simple and effective. Their enduring design and reliability make them the backbone of malt whisky production.