The Structure and Classification of Pot Stills in Whisky Production

In whisky production, the pot still is a traditional and indispensable piece of equipment. Depending on its function, it is generally divided into two types: the wash still (used for the first distillation) and the spirit still (or low-wines still, used for the second distillation). The combination of these two stills effectively increases the alcohol content and helps shape the distinctive character of the spirit.

Functional Classification

1. Wash Still

After fermentation, the wash typically contains about 8 % ABV alcohol. It is charged into the wash still and distilled, raising the alcohol strength to approximately 23 % ABV. The resulting distillate is known as the first distillation spirit or low wine.

2. Spirit Still (Low-Wines Still)

The low wine is distilled again in the spirit still. During this stage, the distillate is separated into three parts:

Foreshots (Heads) – the early portion, containing undesirable compounds;

Heart (Middle Cut) – the desirable portion, which will be matured;

Feints (Tails) – the final portion, containing heavier compounds.

Only the heart cut is selected for aging, while the heads and tails are often recycled and mixed with the next batch of low wine for redistillation. Spirit stills are generally smaller in capacity than wash stills.

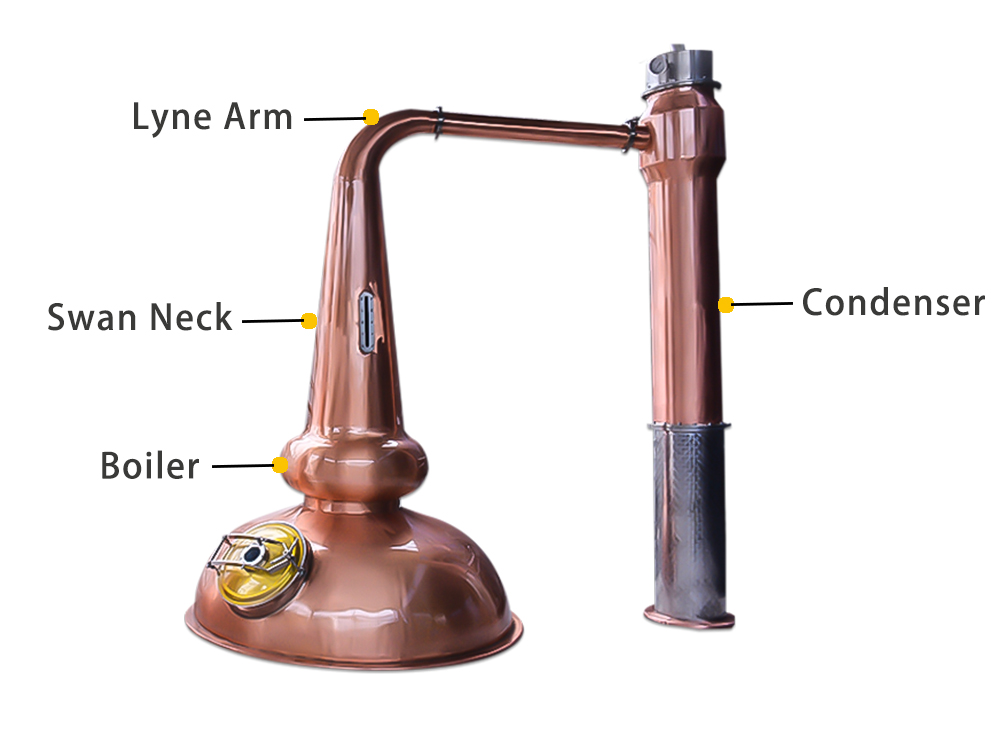

Structure and Technical Features

The design of a pot still varies greatly, and each element plays a significant role in shaping the whisky’s final style. Distilleries select specific shapes, sizes, and configurations to achieve their desired spirit profile.

1. Boiler

The boiler is the main vessel that holds and heats the wash. Its size and shape directly affect batch capacity, heating efficiency, and vapour dynamics.

Copper is the preferred material for pot stills—not only because of its excellent heat conductivity but also for its ability to react with sulphur compounds, thereby reducing off-flavours such as rubbery or sulphurous notes. This purification process enhances the overall smoothness and purity of the distillate.

2. Swan Neck

The swan neck, located at the top of the still, connects the boiler to the lyne arm. It may be shaped like an onion, lantern, or bulb, depending on the distillery’s design.

The height and curvature of the neck significantly influence the level of reflux—the process by which rising vapour condenses on the copper surface and returns to the boiler.

Greater reflux produces a lighter, more delicate spirit, as volatile compounds are refined through repeated condensation and evaporation.

Less reflux yields a heavier, more robust whisky with stronger character.

Generally, taller and narrower necks promote reflux, while shorter and more direct designs create fuller, oilier spirits.

3. Lyne Arm

The lyne arm is the copper pipe extending from the swan neck to the condenser. Its angle, length, and orientation (upward, horizontal, or downward) have a major influence on the final spirit.

An upward-angled arm encourages reflux and leads to a lighter spirit, while a downward-angled arm allows heavier compounds—such as fatty acids and esters—to pass through, creating a richer whisky.

Some distilleries install a purifier or U-bend return pipe between the lyne arm and the condenser to send heavier vapours back into the still. The distiller must carefully balance these parameters to achieve the desired flavour profile.

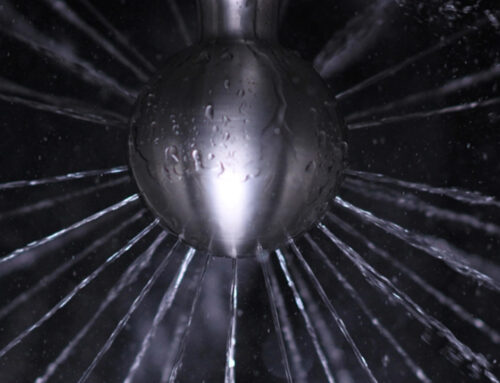

4. Condenser

The condenser cools the alcohol vapour into liquid form. There are two common types used in Scotch whisky production:

Worm Tub Condenser – A traditional design in which a coiled copper tube (the “worm”) is submerged in an open water tank. Because the vapour contacts less copper, the resulting whisky retains more sulphur compounds and heavier flavours, yielding a full-bodied and robust character.

Shell-and-Tube Condenser – A modern vertical copper cylinder filled with numerous fine tubes. Cooling water flows in the opposite direction to the vapour, increasing copper contact and promoting a cleaner, lighter spirit. Most contemporary Scottish distilleries have adopted this design for its efficiency and consistent spirit quality.

A pot still is far more than just a vessel for heating and evaporation—it is the heart of whisky style creation. From the wash still to the spirit still, and through each structural element—the boiler, swan neck, lyne arm, and condenser—every design detail subtly influences the whisky’s aroma, flavour, and texture.A well-crafted still design allows a distillery to produce a spirit that embodies its unique character and signature house style, preserving tradition while defining individuality in every drop.